Second Season: Podcast Episode #9

A Feeling of Comfort

The women of Gees Bend used anything and everything that came to hand, and over time they honed their skills and their designs. Isolation, poverty, and a strong community spirit nurtured an acute eye for colour and design that is unequalled. It took 100 years for their work to be properly appreciated, and when it was, the critics believed that the work of the quilters prefigured the work of the Modernist Art Movement. This is the story of the quilters, how they grew up, and how they work. It tries to answer the question of how they took quilting to the level of great art.

Thanks go to Mary Margaret Pettway and Loretta Bennett for giving me so much of their time and insight, and to Raina Lampkins Fielder for her clear-eyed understanding and appreciation of the artistry and context of the Gee’s Bend quilters.

Souls Grown Deep Foundation: www. https://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/soulsgrowndeepfoundation/

Gee’s Bend quilts on Etsy: https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/GeesbendPlace?ref=simple-shop-header-name&listing_id=972534169

And an article about the quilters for the Etsy Journal: https://blog.etsy.com/en/gees-bend-quilters/

If you would like to sign up for your own link to the podcasts as they are released, for extra information and a chance to access the free textile gifts that I’ll be offering for each podcast in this series then please fill out the very brief form here or find it on the Haptic and Hue Listen page.

If you are interested in a long read or two, or want to know why and how cloth speaks to us then you can find articles at www.hapticandhue.com/read

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name. You can see more of my work and that of other makers there or on the website.

Gees Bend 1900

Quilting Gees Bend 1937

Homes in Gees Bend 1937

Annie Bendolph – a deeply talented

quilt maker 1937

Interior of a home 1937

Annie and Jacob Bendolph

and their children 1937

Loretta Bennett

Workwear Quilt, Loretta Bennett

Loretta Bennett

Loretta Bennett

Mary Margaret Pettway

Mary Margaret Pettway

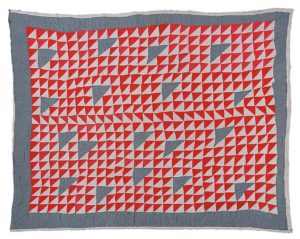

Annie Bendolph Thousand Pyramids

Blocks and Stripes

Loretta Bennett

Raina Lampkins Fielder, Curator,

Souls Grown Deep Foundation

Think of great art: what does that thought conjure for you? One of Van Gough’s intense sunflowers, Leonardo da Vinci’s enigmatic Mona Lisa, or perhaps a Monet painting of Lilies, and a Paul Klee full of tumbling colours.

These immediate thoughts tell us a great deal about our own societies, societies that have come to place things that are seen, painting and sculpture, over many other art forms, certainly over things that are felt or touched.

It also tells us that we have usually seen great artists as lone men, usually white, working out of their own, often tortured genius.

But supposing we stand this idea on its head and ask if art can emerge in a different way, instead of being the creation of an individual, can it come out of a community and can the expression of that art be the product of ideas and innovations that are explored together and transmitted freely from generation to generation Let’s add to this idea that this community might be as far from privileged as possible, the artists here are extremely poor women of colour who struggle.

Sounds unlikely? – but it’s true, for around 100 years or more in a small isolated township on a deep curve of the Alabama River in the Southern United States called Boykin or Gee’s Bend, the artistry and skills of a community of women working with textiles has grown and strengthened.

It took time for the formal art world to be able to see them and recognise them as trail blazing artists who pre-figured much of the modern art movement, even though they never had a formal arts education.

But that says more about the art establishment, than it does about the women of Gees Bend. And once the critics were able to see them they were largely thrilled and excited. I remember seeing these quilts for the first time and they really knocked me in the eye: they are fresh and utterly original, and each one tells its own story, as well as that of the wider community they are made in.

When he first saw them Michael Kimmelman, an art critic of the New York Times called the quilts:

some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced.” adding, “Imagine Matisse and Klee (if you think I’m wildly exaggerating, see the show) arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South in the form of women, descendants of slaves when Gee’s Bend was a plantation.

Welcome to the second series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles. I’m Jo Andrews, I’m a handweaver interested in how cloth speaks to us and the impact it has on our lives.

Each of the episodes in this series takes an emotion and unravels how we express that feeling in textiles. This time we look at one of humanity’s universal needs – A feeling of comfort, and to do this, this story looks at the quilt-makers of Gee’s Bend who have produced work that has challenged our ideas about art and changed our perceptions of what it is. This podcast tries to answer the question of how the women of Gee’s Bend achieved this in the process of creating comfort for their families.

Well, it was cold down here. We didn’t have a whole lot. I mean, you know, in the way of keeping your children are warm and stuff like that, we didn’t have a whole lot. So we, we took what we had and we made what we needed. If you needed a quilt on the bed, that’s what you made. If you needed a quilt to hang to the windows. Cause those old houses, those were really raggedy. Some of them, right? No insulations in the walls. And some of them were in such bad shape. You can actually look through the floor onto the ground, and still, you don’t want your children to be cold, you know? So you made them, you made enough for, to hang on the wall, to spread on the floor, to spray it on the wall, to hang over one plus the bed

That’s Mary Margaret Pettway and when she says: we didn’t have a whole lot, she means that in a way in which would be hard for many of us to grasp. There are some good photographs of Gee’s Bend taken in the 1930s, some of which I’ve posted in the show notes for this episode. At that time people were living without running water or electricity in incredibly ramshackle log cabins. They used newsprint to line the walls. Things did change somewhat, but it has never been easy:

We grew up poor. Okay. Lot of people had gardens. Lot of people had house. A lot of people had cows. And if you had all three you’re had enough out, you were rich. Okay. So it used to be, if somebody killed a hog or a cow, everybody around the community would get some meat, you know, a little, a little thing, a grease to cook with. You know, if somebody had a garden and you didn’t have one or something was growing in their garden, that you didn’t have you can go to their garden or go to them, ask them for it. And they would give it to you.

The families of Gee’s Bend were subsistence farmers with their own animals, and gardens, and some pay from picking cotton, something that the whole community was involved in from early childhood. Here’s Loretta Bennett who is Mary Margaret’s cousin.

And, and, you know, you had to be in the field, you know, to pick the cotton in and that going to be like from sun up to not, you know, almost sun down time to get it all out of the field before it, you know, the raining season come. Actually even five years old and six years old, they didn’t, they didn’t necessarily pick the cotton, but they were, you know, they may have to bring water to the ones that was out in the field doing the picking. And so they would have to carry the water out and give you a drink of water. So it kind, everyone got a kind of had a Sherry in it, even babies moms had to bring their babies. You know, the babies may get pulled on the side of the, you know, where you put the cotton inside as they was picking it.

And if you wanted curtains, for your home, covers for your bed and insulation on the walls you had to make quilts. It is out of this necessity that the artistry and skill of the women of Gees Bend originates. Mary Margaret says they used anything and everything for quilts:

What if they can get their hands on, believe it or not, they would use seed sacks and take time and rip them. And actually if you rip it just right, you can save the thread so you can do what they call used to call hooping in a quilt with it. And they use feed sacks, old pieces of sheet, old pants, old dresses, old shirts, you know, just whatever they can get their hands on.

And here’s one element in the originality of the Gee’s Bend Quilts, the ability to make use of anything that comes to hand. The Pop Art movement developed in the 1950s and 60s in the UK and the US with its rejection of ‘museum art’ and its embrace of the ordinary and the commercial. But the women of Gees Bend had got there long before that, because they had to.

Both Mary Margaret and Lorretta are accomplished artists. Their quilts hang on the walls of museums and galleries round the world. They have no formal art education but Gees Bend was in its own way a tough school, both of them describe themselves as growing up “under the quilt”. Here’s Mary Margaret:

We grew up in the, in the sixties. We grew up under the quilt, which means if your mother had a quilt up, that’s where you were up under that quilt. So you can thread them needles and stick them back up through the quilt or hand them to them. But we took naps of under too. We some of the old quilts, they spread an old quilt after they have the quilt set up, they spread a really old raggedy, quilt up under there for the children to sit on and play with and practice their ABCs and stuff on. And yeah, so it literally means growing up, well, you didn’t grow up on it, but you know, being under the quilt when they were quilting it.

And this was very much a family activity, women did not quilt alone – they learnt from each other and passed ideas amongst themselves, as Loretta explains:

It’s what you call a quilting bee. You know, it might be like my mom, her mother, and some of my mom’s grandmother, auntie, something like that. You know, they would take turns going to each other’s houses, maybe, maybe you know, they’ll go to this person, housing quilt, all of their quilt tops that they’re made, you know, they, they made by themselves the quilt top and what they would do. They would go to different houses and Quip the quilts up, you know. I can that I know of go back to my great great grandmother which her name was Diana Miller. And so we can go back to that, you know, distant.

There’s a black and white picture taken about 1900 of a woman, who is undoubtedly related to Mary Margaret and Loretta, tending some quilts that are airing over a fence. The quilts in front of her are startling in their originality. In Gee’s Bend these were almost impromptu exhibitions, everyone got a good look at your quilts as you aired them, and critically appraised them, gathering scraps of new ideas for themselves. This is one of the ways in which their artistry was valued and honed. And once girls emerged from the play den under the quilt, they too found themselves set to work

I was about six years old, you know, just threading needles. And sometimes like in the summer months when my mom, my grandmother was piecing quilts they have some little pieces that they may not want to use and they, you know, they would let us practice on them. But when I got about 12 or 13 years old, one summer, I decided I was gonna make this, this quilt. For some reason, I don’t know why, but my mom had a lot of octagon shape pieces already cut out. it’s called a flower garden and I decided that I was gonna make this quilt and I made it, it took me all long someone on it every day, just about all day, you know, except for when I had to go do some chores around the house. And and it came out all crooked, but anyway, my mom kind of straightened it up and she, she you know, quilted it later. It made me feel really good. It was like I had something to do that summer.

For Mary Margaret it was harder road:

Quilting was like a punishment for me, I think. And I say that because I was made to learn to quilt. You know, when you’re a child, you want to go out and play with everybody else. But my mother wasn’t having that. She I don’t care who’s in the yard or came to play if she wanted you to do your quilting. That’s what you did.

Both Mary Margaret and Loretta make original and lyrical work, but Loretta is clear that the traditions in which they quilt are drawn from their ancestors.

Well, I think I drew mine is from, from just looking at my mom’s quilts and the other ladies quilts and just looking at the way that they use, you know, used what they had. Most of my quilts are used from coping and so repurpose clothing in. And so I like to use that. And as sometime I just let it make themselves and with a little music.

So we have lots of elements that go to make up the skill and expertise shown in Gee’s Bend, but still there is an extra magic there. A flame of creativity, something special in their understanding of design and colour that has allowed generations of women to produce astonishing work. Mary Margaret and Loretta have slightly different explanations for this. Here’s Loretta:

Oh, I think, cause we, maybe, because we was isolated in this little bend of the river, you know, one way in one way out. So we was not exposed to any type of artwork or a lot of television or anything like that. We had television, but you only got so many channels, not that we knew we were making anything extraordinary. It was just that we wanted something, I guess you would say pretty and that we wanted to have on our beds or even hanging out on the wire to drive it just that it was our way of expressing our, you know, our own individual creativity, I guess.

For Mary Margaret its more of a puzzle:

I, you know, I wish I could answer that question. I don’t know. I mean, I look at some of the quilts and even some of the ones my mother did and answering truthfully, I wonder what was going on in her mind. Okay. I think they had an eye for what would be popular. You know, a lot of quilts down here, they have that little piece of red in it or an odd color, you know, there’s not like the other ones, even with denim, you know, you got dark denim, you got light denim and denim shows the wear pattern in it, in the wash pattern in it. But you got that odd piece where it might be everything else might be old, old, really old washed and softened denim. And then you might have a new piece or something that looks like a new piece where they may have taken a pocket off. And that piece is beautiful up under there. It’s like new denim.

Raina Lampkins Fielder is the curator of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, it is dedicated to documenting, preserving and promoting the contributions of the African American Artists of the American South and the cultural traditions from which they grew. The words Souls Grown Deep come from a wonderful poem written by Langston Hughes. Raina believes that part of the explanation for the artistic talent of Gees Bend comes right out of the hardship and experience of discrimination:

If you’re going to do something, you do it for yourself. And so that kind of spirit, and I think that’s just part of the African-American experience in general is that kind of, I think, led to allowed for them allowed for the quilt makers and Gee’s bend to really go their own way, as they say, to do my way quilts where it’s like, okay, we might start on one on one route, but let’s see where it takes me. Let’s see what I can create within these borders that is transformative and, and bigger than the borders themselves. You didn’t have to play by a certain sort of rule because the rules were not, the rules were only there, the larger kind of societal rules to hold you back. So where can you find your own sort of freedom and articulation of yourself within something that is about muting what you have to say. And so, you know, if you’re a little bit more isolated, well, you can do what you want. And I think that is one of the things that kind of leads to that. Gees Bend style that almost indefinable Gee’s Bend style that is so captivating to the rest of us, looking in on what is produced in that area, because it’s like almost this tug and pool between a restriction of the border, but then all of the majesty and improvisation and, and intention and story and, and biography and art that can occur within those, those borders. We see that there’s something there’s something different about it. We feel it, we sense it.

It took time for an understanding of what was happening in Gee’s Bend to seep into the outside world. Raina says it was a slow burn over many decades for the quilters to be appreciated:

Well, it’s interesting because I think that there have been many sort of sudden moments when people refocus their lens and maybe expand where they’re looking to see some of the amazing work that’s being made in the United States and in the South. I would say probably the, the time that is often noted as being that moment when people really saw what was going on in the community was in 1937, where a photographer Arthur Rothstein was basically taking survey photos of tenant farmers in Boykin, Alabama, and Gee’s bend is within Boykin, Alabama. And from that we saw women quilting in their homes, and we also saw some of the quilts that were being aired outside. So it became this, you know, a kind of unexpected exhibition of the work that was being created in these domestic spaces, then being outside hanging on lines to be aired naturally. And so that was one of the first times that people thought, Oh, what is going on in this area of the country.

And then after that, nearly 30 years later, some of the artists of Gee’s Bend become involved in the Civil Rights Movement, and set up a Freedom Quilting Bee.

And then of course with the establishment of the freedom quilting bee in 1965, again in Gee’s bend Alabama, this was another moment when people began to see and hear about what the quilt makers were doing then. And also just to give it a little bit of context, the quilts really have a history. Particularly at that time, that was deeply in the civil rights movement in Alabama. And so the freedom quilting bee, the freedom quilting bee cooperative was established in 1965. And, and this was established by two quilt makers. And this was a way of sort of transforming the economy of the area. They understood what that the quilt that they were producing and also their sewing skills could be used outside of the bend.

Their involvement in the Civil Rights Movement and its impact on their lives was profound in many ways, it was also extraordinary that even their political involvement was expressed through textiles: Here’s Raina:

I think that the injustice certainly for African Americans, you know, there’s never been a revelation of injustice that has been a sort of constant state. I think it was though in the sixties when one could become more politically active when it was a little bit easier to do so still a challenge, still a challenge now, but certainly still a challenge in the South at that time. I think with that combination of demanding larger civic rights, voter rights equal pay opportunity, that one then looks at what one has that can be used for political gains that can be used for just opening up a community and making it diversifying what is possible for our community. I think that was that point where the freedom quilting bee was able Use what they had. I mean, that’s, that’s what and use what they had to, to for a greater good, whether that greater good is trying to find some sort of economic equality or to at least improve economics situations to also promote one’s voice. And to show that there is something quite unique in this area, even the spirit of the community that was taking that was taking on their role within the civil rights movement as well. So it’s, that was that moment just in the United States of a larger political action, very much married to civil rights.

But the explosion of public interest in their work had to wait until the early 2000s. By this time a collector and supporter of African American art, William Arnett, had arrived in Gee’s Bend and started paying better prices for their quilts. And then finally in 2002 the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas and the Whitney Museum in New York showed the first exhibitions of work from Gees Bend. And the critics raved, but at first it was a puzzling experience for artists as Loretta explains:

And I would have to share that when I saw him in Houston for the very first time or, you know, hanging in a museum, it was just, it was just so mind blowing, you know, the clips that we thought were so ugly and, and you don’t just was used for necessity, you know, just to be laying down on or just to be covering a window of Florida, keep the air out. And now you see CDOT, very sane quilts that you laid on hanging in a museum that is so old. It is so, so powerful. It, and, it brought tears to our eyes.

And then other museums followed suit, even the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York held an exhibition and the women of Gee’s Bend went to see it.

So the other quilters, they were like me. They could not believe it. They were like at first we all was like, I don’t know what they see. And but at it, as each museum went on and on, you know, we went to different museums. Some of us still didn’t see what they saw, but it began to dawn on me that these quilts are very beautiful. These quilts are our art, you know, even though we, then, you know, we had no idea of what art was because, you know, we were so isolated. But some of us younger ones got it when the older one that has passed on, they still did not, you know, they did, they didn’t comprehend, you know, what the quilts, how beautiful the quilt was.

The first time Mary Margaret ever went to a museum was to see the Gee’s Bend Quilts at the Met in New York, she found it an overwhelming experience.

And I, myself was so excited because all those old quilts, the ones that were under the mattresses and packed back, you know, on a shelf in somebody’s room, they looked beautiful, hanging up on those sterling white walls, those quilts look like they would just the most prettiest things in the world. And the one at my mother has one at the met, and I saw it and I forgot I was in company. You know what I mean? So I used to sleep on it, that old thing, man, you know what I’m saying? I didn’t know I was saying it aloud, but it came out and everybody was looking at me like, I’m going crazy.

To me the quilts have the elegance and emotional power of blues music – which also originates in African American experience in the Deep South and draws its traditions from work songs and spirituals. And just as the blues have brought us something new and profound, so too has the work of the artists of Gee’s Bend

If life is really challenging for anyone, regardless of where your position ultimately is monetarily socioeconomically, or even geographically to a certain degree you know, so that’s just kind of part of how the system is just not so great and, and upholds and empowers one group to the detriment of another. But that doesn’t mean that that is what entirely defines that person or that area or that group. That’s just a part of the context, but what’s being created where their voices really reside is what they are sharing with us in the works that they create in the choices that they make in the stories about themselves or labor or their family that are articulated in these works that are incredibly thoughtful.

Both Mary Margaret and Loretta still live in Gee’s Bend, but despite the acclaim they have received, they fight shy of being called artists. And that’s partly a reflection of how hard it has been, for women and in particular women of colour to claim this space and this title, when it has shut them out so comprehensively. Loretta says it takes a bit to get your head round it.

Yes. It is weird. Because I don’t see myself as being an artist. I still see myself as making been a quilt maker

The Quilts and the quilters themselves have brought Gee’s Bend acclaim and as Mary Margaret says, a level of financial security:

It gives us options. I would say in the saying that if you are lucky enough to sell a Quill, then you don’t have to decide, well, I can just pay this this month on my bills. You know, pretty much everybody’s in debt. You know, some of those debts you can actually pay off you can get your house fixed, you can get a car or do a down payment on a car or truck, you know, and all of that gives you it’s meaning freedom basically.

At the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Raina Lampkins Fielder believes the quilters of Gee’s Bend have broadened our perception of art and Raina has her own explanation of why the artist quilt makers of Gee’s Bend are unique:

Quilt making and, and the reuse of materials in various ways, one finds this in many communities. But in Gee’s Bend, it became part of the, the way of looking and being, of interacting, of communicating with each other, been such a longstanding tradition of the transmission of quilting techniques for over a hundred years. That’s something that is unique to that place. Sometimes you don’t know exactly what’s in the water in places, but it’s very difficult for me to think of another artistic community or creative community that continues to this day to make work of this quality and with an intention of doing something perhaps a little bit different.

Mary Margaret and Loretta are both active quilt makers – extending and growing their experience and incorporating new ideas. But beyond that they both say that the quilting brings them something special, here’s Mary Margaret:

And quilting, I am at a, what they call perfect peace. If I’ve got background noise, like a TV or radio, and I’m warm, sometimes my children will actually (Feed me and I’m perfect. I can do it all day, just sitting there. And that is a quality of life that is so very hard to find. Now

And for Loretta It’s a way of centering her in her own community and family:

So, and I just, you know, I kind of go back to the time when they, my parents, my great, great grandparents when they was making quilts, I don’t know how you would say it. I kind of feel like they are with me when I’m, when I’m doing, you know, my sewing. I can, I can feel like they are there with me.

This episode of Haptic and Hue was narrated and edited by me, Jo Andrews. If you go to my website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen, you will find a full script of this podcast pictures and links to the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and the Etsy site where the Gee’s Bend Quilters are selling their art. You can also sign up there to get these podcasts directly in your in-box, as well as having a chance to win some of the textile related gifts I give away with each episode.

Thanks go to Mary Margaret Pettway and Loretta Bennett for giving me so much of their time and insight, and to Raina Lampkins Fielder for her clear-eyed understanding and appreciation of the artistry and context of the Gee’s Bend quilters.

Thanks for listening and I will leave you this time with the last verse of the poem by Langston Hughes from which the name of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation is drawn. Hughes was a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920’s in which many Black intellectuals and artists flourished. It is read by Bill Taylor.

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.