Canada’s Forgotten Quilts

Episode #26

This episode of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles begins with a mystery quilt that turned up on a cold winter’s morning 30 years ago. The quilt had an old handwritten label on it, but we could find out almost nothing about it or how it came to be made. This tale uncovers the astonishing story that this quilt was part of – the story of how millions and millions of items from bandages to sheets, from pyjamas to quilts were made by Canadian women and children as ‘comforts’ to send mainly to Britain in the Second World War, but also later to The Netherlands, France, and Germany. They went to help those who had lost their homes and all their possessions. We hear from one of the last people alive who made these quilts during the War, and also from someone who was a baby when she was bombed out of her home and received a quilt. It looks at the impact the quilts had on the people who were given them and thinks about why this amazing effort has been ignored and almost completely forgotten. It speaks to those who are trying to restore these quilts to Canada’s national memory.

Joanna Dermenjian can be found on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/suture_and_selvedge/ Her website is at https://sutureandselvedge.com/ where she blogs on any updates and news. You can contact her directly at Joanna.dermenjian@queensu.ca . Joanna also keeps an inventory of all the quilts that have been repatriated to Canada. So far she knows of 12 that have come home. She continues to piece together the definitive story of these quilts.

Maxine March and the Canadian Red Cross Quilt Research Group keep the inventory of quilts and their whereabouts, you can see more about their work and report the existence of a quilt at: http://crcq.co.uk/ or directly at http://www.crcq.co.uk/contact_form.html?CRCQ_RG

Jan Hassard’s website is at https://www.janhassard.com/ She is on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/janhassardquilting/

If you are interested to see more of the quilts then there is a book called Comfort From Kindness which you can find https://www.weavingmusicalthreads.com/shop/56-comfort-from-kindness-wwii-canadian-red-cross-quilts NB you need to ring them if you want to buy the book – they are in the UK.

Here are some other online links to Museums and Institutions that hold Canadian Red Cross Quilts and have information about them.

https://americanmuseum.org/red-cross-quilts-from-wwii/

https://www.nationalquiltregister.org.au/quilts/canadian-red-cross-quilt/

http://www.quiltmuseum.org.uk/collections/heritage/unknown/1940-1950/canadian-red-cross-quilt1.html

http://www.quiltmuseum.org.uk/collections/heritage/unknown/1940-1950/canadian-red-cross-quilt.html

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1322216/canadian-red-cross-quilt-patchwork-quilt-unknown/

https://www.redcross.ca/history/artifacts/canadian-red-cross-quilt

You can follow Haptic and Hue on Instagram @hapticandhue on Facebook or Linked In under the Haptic and Hue name.

Jo and The Mystery Quilt

The Winona Circle Quilt

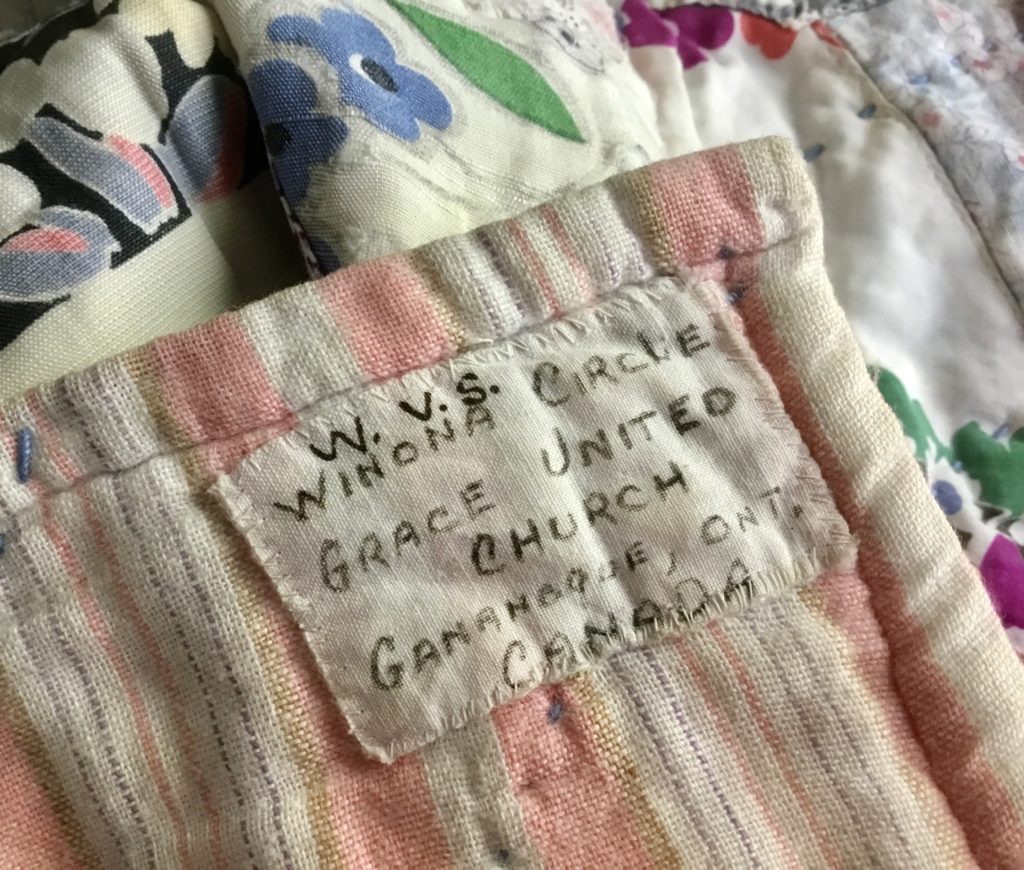

The Quilt’s Handwritten Label

![WIF53-1-030-1 Hillside Group Red Cross Quilt, [1940-1945] [from Kemble Women's Institute Tweedsmuir Vol. 1]](https://hapticandhue.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/WIF53-1-030-1-Hillside-Group-Red-Cross-Quilt-1940-1945-from-Kemble-Womens-Institute-Tweedsmuir-Vol.-1.jpeg)

Kemble Women’s Institute, 1940-45

Image Courtesy of Grey Roots Museum and Archive, Ontario

![WIF28-1-9-1 Red Cross Quilting Meeting, [1940 -1945] [Zion-Keppel Red Cross, from Zion and Wolsely Women's Institute Tweedsmuir History Vol. 1]](https://hapticandhue.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/WIF28-1-9-1-Red-Cross-Quilting-Meeting-1940-1945-Zion-Keppel-Red-Cross-from-Zion-and-Wolsely-Womens-Institute-Tweedsmuir-History-Vol.-1.jpeg)

Zion and Wolsely Women’s Institute, 1940-45

Image Courtesy of Grey Roots Museum & Archive, Ontario

![WIF70-1-055-1 Red Cross Quilting, 1944 [from Sarawak Women's Institute Tweedsmuir History Vol. 1]](https://hapticandhue.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/WIF70-1-055-1-Red-Cross-Quilting-1944-from-Sarawak-Womens-Institute-Tweedsmuir-History-Vol.-1.jpeg)

Sarawak Women’s Institute 1944

Image Courtesy of Grey Roots Museum & Archives, Ontario

The girls of remote Torun School in Alberta create a quilt for the war effort. Photo courtesy of South Peace Regional Archives, Peggy Mair Fonds.

Phyllis Vanhorne, 1939

Phyllis Vanhorne 2020 – Still Quilting

Jan Hassard

A Quilt in Dresden Plate Pattern Similar to Jan’s

The Quilt Jan Found at the Antique Fair

Traditional Label on Jan’s Quilt

![IMG_8125[1]](https://hapticandhue.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/IMG_81251-1024x768.png)

Maxine March who set up the Research Group with Two Friends

Maxine’s Collection of Quilts – She Never Turns One Away.

Annie Scott with Husband George. Photo credit Bill Fitsell, Kingston Whig Standard

Quilt All Packed Up and Ready for Its Journey Home

Off to Canada After 80 Years!

Canada’s Forgotten Quilts

Remembering Women’s Work in War

Sometimes the story of a cloth hangs by a thread, or in this case a thread, a chance, and a co-incidence all bundled together. The tale in this episode is one that has never been properly told since it began more than 80 years ago. It has come close to sinking out of sight completely. It’s about an astonishing operation by the women and children of Canada to provide help, comfort, and consolation to thousands of men, women, and children in Britain and Europe in desperate circumstances during and after the Second World War. It deserves to be remembered and honoured but instead, it has been forgotten – even in Canada – just as the very last survivors of the generation who took part in it are leaving us.

In the long term, sometimes I think we’re so close to our history that we don’t really see the importance of it until we get a little farther away. And then suddenly we look back and go, oh, we never really talked about this. We never learned from this. We never made a record of this. And it’s too late now because the women who participated are gone and there, or journals are they, their journals, the quilts in the sense are their journals. The quilts are the only items left from the things that they made that are still in existence. The bandages are gone and the sheets are gone and the socks are gone, but they are two or three hundred surviving quilts in, in Canada, in Britain and Europe, they tell the story. And I think it’s really important that that story be recorded.

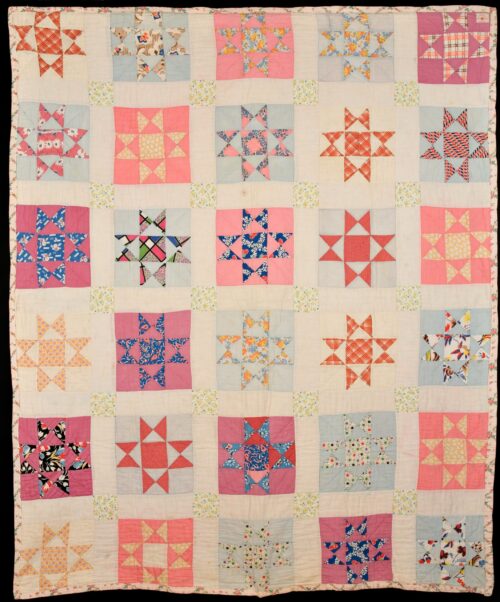

That is Joanna Dermenjian and we will be hearing more from her in this episode, in fact, it could not have been made without her. Welcome back to the third series of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles, which is called The Chatter of Cloth. My name is Jo Andrews and I am a handweaver interested in how textiles speak to us and in trying to unravel the meaning they hold in our lives. My part in this story started 30 years ago – one cold winters morning when I was helping my mother collect blankets to send to the Kurds in Iraq. They had fled into the freezing mountains to escape Saddam Hussein’s murderous army. Blankets were the least we could do for them. At the end of the morning, we sorted through the donations and found a quilt, an old hand-made quilt with a striped cotton backing. It had a handwritten label that said: WVS, Winona Circle, Grace United Church, Gananoque, Ontario, Canada. The fabrics that made up the front of the quilt were 20th century, probably, to our inexpert eye from the 1930s or 40s. I have no idea to this day if we did the right thing, but, we made a donation to the Kurdish Relief Fund and kept the quilt. We never saw who gave it in and we will never know what their motivation was in doing so. It is a joyful thing and very much of its time. The quilt was made from what looked like dress fabrics shaped into different square blocks, any which way so that no piece of fabric was wasted. It was then hand quilted with blue thread and a pink and blue backing fitted to it. It was made for a single bed, and, even though it is composed of many materials it works – it looks as though it belongs as a single piece. For many years we could find out absolutely nothing. It was a puzzle. My mother tried ringing the Grace United Church in Gananoque – they told us that they knew nothing about a quilt or the Winona Circle. And then in 2010 the Victoria and Albert Museum held its memorable Quilt show. In amongst all the grand and the great quilts was a much humbler one that said: Bedcover: Maker Unknown, Canada: This quilt was made by the Canadian Red Cross Society as part of its initiative to provide relief for civilian victims of the Second World War. It was clearly a relation to our quilt, so now we had an idea that ours was a Canadian Wartime Quilt. More years passed and then late last year, I got an e-mail out of the blue from Joanna Dermenjian in Canada asking to be considered for one of the free gifts Haptic and Hue gives away with each episode to subscribers to the newsletter. Joanna signed her e-mail with the strapline: Researching Canadian World War 2 Red Cross Quilts, and guess what her postal address said? Gananoque. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Joanna had started researching Canadian Red Cross quilts while working on her Master’s Degree looking into women’s practice of stitching for leisure:

And so my, my supervisor asked me to find one artifact that I could centre my research around in order to talk about this. And somehow on the internet, I found a red cross quilt. It popped up, I think, on my Pinterest feed and I read a little bit about it on the Red Cross website, the Canadian Red Cross website. And I was really intrigued by this little label and the, the description said that these quilts were made by women in Canada during World War II. So I just started to look for more information about them. I was so surprised I couldn’t find any, there were brief mentions, in Canadian quilt books but not in journals. And I was quite new to the whole idea of researching in primary sources. So I talked to the librarians and, you know, went through what I was looking for, and she agreed with me just as she did sort of some precursor research. She couldn’t find anything written about these quilts either. So it, I chose this as my topic because I was very interested in getting this story told and getting an understanding of what the story really was.

What Joanna uncovered astonished her. During the Second World War, 55 million items went from Canada to Britain. These items were called comforts and most of them were made by the women and children of Canada.

There’s a long list of items that they made. They were, they were sewing for the hospitals. They made sheets and bandages, pajamas and slippers and robes. They even made cloth face masks for surgeons. And then we know that they were also sewing for the people of Britain who lost everything in bombing. And they were the Red Cross supplied patterns for sewing things like jump and skirts and all kinds of different basic items that people would need. I even found an article. This was so sweet that they were the Red Cross asked that women not used very bright colours in the clothing that they were sewing for the people of Britain, because the people of Britain didn’t quite like them to be so bright <laugh>, isn’t that cute?

Amongst this multitude of items were more than 400,000 quilts which were handmade by women and children in Canada. This seems to have been suggested by the Canadians themselves and it looks as though they wrote to Queen Elizabeth – later the Queen Mother – to ask her permission to send the quilts. Permission was granted and every conceivable kind of organisation across Canada got involved.

What I have found is that they were made by groups of women but many different kinds of women’s groups. So in Canada, there were the Women’s Institutes, which is primarily a rural-based community group. The Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire is another group of that time that was very popular and very active. But they were also being made in churches and in Jewish synagogues, they were being made in homes. They were being made in Red Cross workrooms, there were some Red Cross workrooms before the war, but during the war, they increased exponentially and they would be formed in libraries and other community buildings where women could meet regularly, I even found a red cross workroom at Queens University in the very building where I was taking some of my courses. There had been a Red Cross workroom and female students were making quilt blocks around 1942 and 43. There’s a picture in one of the yearbooks of young female students working on quilt blocks.

And there are pictures too of school children working on quilts in remote rural schools in Canada. Every quilt was different and each quilting group found its own materials, although later the Red Cross supplied the batting and the backing cloth. Joanna has done a quick calculation of the time that went in to make the quilts:

I ran some rough numbers to say that even if a quilt is constructed by machine. So if the quilt top is made by a machine, but then the quilting is done by hand, there’s still about 50 hours that would be invested in, in making a quilt 50 hours, women, hours of work to complete a quilt. And the women made over 400,000 quilts in a six year period. It is 20 million women hours of work at minimum just to make quilts.

Most of the women who were involved in this effort have long since left us – In Canada the time, skill and the craft they put into this work has been almost forgotten – but not quite. In 1942 Phyllis Vanhorn was a young bride, she had just moved with her new husband to Wooler, near Trenton in Ontario. Her husband worked at the Airforce base there and she found herself with time on her hands, until the local church group found out that she could sew. Phyllis is now close to a 100, but her recollection of those years is clear. Joanna went to speak to her at her home for Haptic and Hue.

Phyllis: Well, I just remembered how we used to spend the days quilting. There’d be the women of the neighbourhood, three or four women would get together and quilt for the afternoon. There was no fancy quilting about it. It was all plain, straight going mm-hmm quilting. You would be maybe meet two hours every afternoon or early evening, depending on how much daylight there was, because there was no lights at that time. No electricity. I had no family and it was a good way to get acquainted with the other women. And I had a big living room and they used to, the women would set the quilt up in my, in my living room.

Phyllis still has all the old quilting frames from her mother her grandmothers and her neighbours stored above her kitchen – every one of them is slightly different. In the war the quilters would often source offcuts from local shirt and pajama factories, and from suiting and military uniform factories and make them into patchwork blocks, carefully making use of every single scrap.

I thought it was an obligation, might as well. Why sit doing nothing. You might as well be quilting, that was your war effort. Everybody did what they could do. Hmm. It was the only sociable thing there was. Yeah. Yeah. They weren’t having afternoon teas or anything like that. They were busy making use of every second.

To begin with, Phyllis says she wasn’t very good at hand quilting – but she quickly became skilled at doing it deftly and evenly. And at the same time as being a communal activity, it was also a good way of deflecting anxiety:

Well, I was always scared that my husband was going to be posted overseas. Mm-Hmm. I mean, that was the first thing you thought of, you know, Airmen there were airmen everywhere, you know, because we lived at Wooler and Trenton was the main airplane, airport, lots of airplanes all day long in the air.

And that sense of anxiety and unease seems to have hung over many Canadians during a war in which so many of them were directly involved. Phyllis herself likened it to the sense of anxiety she felt at the start of the COVID epidemic and Joanna believes that quite apart from meeting the needs of people at war in Europe the quilters also benefitted from their own work.

Well, I think there are, there are two different things that I’m looking at is women. There was a benefit to the women individually, and there was a benefit to the women in the group setting. So we know that stitching by hand is repetitive and can be a very meditate activity, which is soothing to our spirits. But I believe that gathering together in the community, meeting together provided another layer. Another element to this, where women could meet with each other talk about their weak, talk about what was going on, share tips, help each other learn to stitch. We see in some of the quilts, the stitching isn’t done very well, but there weren’t any sort of judges saying how many stitches per inch. So, I, my sense is that the gathering together would’ve been encouraging, Phyllis told me that she enjoyed meeting once or twice a week with this group of women who were sewing because it gave her something to look forward to and a time to be together.

The quilts and all the other comforts went to the Canadian Red Cross who bundled them up and sent them largely to Britain where they were distributed mainly by the Women’s Voluntary Service and the Women’s Institutes – in another story that has not been properly documented – to people in need: people like Jan Hassard who was a six-month-old baby when she was bombed out of her house in Purley south of London.

So we lived in a typical semi-detached suburban road. Okay. 13 miles from London and they heard the bomb coming over. So it was half or six in the morning. I, everybody was in bed, but I was in the front room. So, therefore, my cot was under a window. So my mother rushed in, took me out of the cot, took me into the back bedroom with her. And the window shattered when the bomb dropped obviously and fell into my cot. So that was a very lucky escape. And, but they didn’t have time to get downstairs. Cause you had two, I dunno if you know about flying bombs, but you had two minutes. So what happened is the bomb came over. They had it, they must have been up. They heard it coming. The engine cut out. They knew it was near, but they didn’t know obviously where it was going. Nobody knew where it was going to fall. They didn’t have time to go downstairs because they didn’t have a shelter. So they used to go under the stairs. Sounds a bit bizarre, but, that was what you did. So she was in bed and I know the wardrobe fell on her and she sort of put me underneath her. I mean, this is all a bit personal, but I am trying to give you a picture of what I understand happened. But obviously, she wasn’t badly injured, but the bomb fell across the road. So you imagine a suburban road with all these semi-detached houses and a hotel across literally across the road slightly to one side. Anyway, we were taken to a centre at a church called St. Barnabus. So, there was obviously a special centre there that people were taken to when they were bombed out. And that is where we were issued with the quilts. It sounds a strange thing to happen. They must have been given other things because they’d had to leave their house. I don’t really know, but all I know is that we could not go back to the house because it was bombed out.

Jan and her family went back to the house in Purley after it had been repaired when the war was over – she remembers the bomb site across the road was dangerous and spooky, and she remembers the quilt stayed on her bed:

I can’t tell you the size, but it was Dresden Plate. I can remember lying in bed. And obviously, the stitching was not brilliant. And I used to pick at these stitches and it was a sort of, I dunno what the wadding was, but it must be some sort of lambswool, I think because I could pull it out and I can remember doing that <laugh> and it had a cream background and I would imagine it was dress fabrics because every patch would be different. Everyone would be different. You see? So the thing is, it was true patchwork true utility patchwork because people would’ve cut up their old dresses.

For those of us who aren’t quilters, a Dresden plate pattern starts with a central circle and then has wedges around it to form a plate-like shape. When Jan was 11 her aunt made her a new bedspread, her room was re-decorated and Jan’s Dresden Plate quilt went to the rag and bone man – one of those people long gone who travelled up and down British streets with a bell shouting “any old rags, any metal”. But that’s not quite the end of the story, because many years later Jan, who became an embroiderer and then a quilter – spotted a Canadian Red Cross Quilt at an antique fair – she knew what it was instantly, bought it and started a collection of heritage quilts, Eventually, she had 8 Red Cross Quilts, before she sold her collection some year ago. Even today she has a business re-creating heritage quilt patterns – so her quilt created an unexpected path for her. Mostly we know the people we make things for and they are an expression of our thought and love for them. One of the things that strikes me here is that the Canadian women and children who made so much never knew who would get what they made or what it meant to them. They weren’t able to put an arm around these people and accompany them in their loss and suffering – but they could offer them comfort through the handwork and the fabric that went into these quilts.In 2005 Maxine March was a member of a quilt group in the UK where she heard a talk about the Canadian Quilts:

When you see one and hold one its history is still there somehow. And I was touched by the very ordinariness of them. None of them would win a competition in a quilt show, but they were all made clearly with affection. The other thing is I realized that it was an aspect of women’s work in the war that had just never been acknowledged. And the impact that those quilts made on people had never been recognized outside of the people who actually received them to the extent that the Canadian women who made them, we found, didn’t always realize the impact that these things had when they got to the UK.

Maxine and two friends set up a Canadian Red Cross Quilt Research Group and a Register to collect details of as many quilts as they could find and their location. They also began to collect accounts of who got the quilts and what they meant to them. The stories just spill out of Maxine:

Of course, the stories come from people who were children at the time, and some of them are quite poignant. You know, there’s the refugee family from the Sudetenland who came over to Britain just before the War broke out who had by the end of the war five children, the fifth one was born just after the war ended. And the mother died within a few weeks. Now the oldest child, a girl of 14 said to her father that she could cope with the three children below her, but she felt she couldn’t take on a newborn baby. So the baby was fostered, but after 11 months was adopted. It was handed over at a railway station with a bag containing a change of clothes and red cross quilts, a crib quilt. She still has it. There’s the story of two sisters who shared a bed and had had a quilt given to them because their house had been damaged by bombing. And at night they used to look at the fabrics on the quilts and take it in turns to choose ones that they’d like to have made into a dress. There’s Betty, who was an eight-year-old living with her Mum in the East End of London. Her father was away on active service. Her house was bombed and her mother was killed, leaving Betty effectively orphaned. She was sent to a Dr. Barnardo’s orphanage in north Wales, and she described how the girls all slept in one dormitory, and on each bed, there was a Red Cross quilt. And at night they used to look at the designs on the quilts and makeup stories about them. And she says, their stories usually finished with a Knight on a horse coming to rescue them. Do you want anymore? there’s a letter in the junior Red Cross Journal in Canada from a little girl of about 11 who was in an orphanage in Reigate and she’s writing a letter of thanks. She says they had the most exciting day when a great bundle of quilts arrived, enough for one each for every child in the orphanage. And the way they were distributed was that the youngest child was allowed to choose first. And so on up through the ages, the little girl writing the letter was the oldest child. So she had the one that was left and she says in the letter, but it’s lovely. And I still like it. And people tended, I think, to keep them didn’t they. And it’s interesting that some of the ones that have come to me have come from the next generation down because they know how much, you know, value their parents put on these quilts.

And even though time passes the stories still keep coming. Maxine’s group has documented the survival of just 250 quilts, most of them in Britain, some are in institutions, like the Quilters Guild in York and the Victorian and Albert Museum in London, some are in private hands, Maxine and the Research Group never turn away a quilt and Maxine herself has 56 – stored at home. She believes that lots of them didn’t survive because they weren’t put away for best – they got used and used:

I had an email some years ago from a man who tells about how his family received quilts during the war. He lived in an area of Devon called Slapton Sands, which was cleared by the military, completely cleared. Everybody moved out, animals were moved off the land because they used the area for training for D-Day. When the families were allowed to go back into their houses, they found that there was a Red Cross quilt on every bed. And he was a child at the time, but he said all his childhood, he slept under his, when he went away to university he took it with him, when he got married, it was used in his home. His children slept under it until the 1970s. By which time of course it was very faded. So it went into the dog basket. And when the dog died, the quilt went to the dump. And I think that’s probably what happened a lot. I mean, I’ve had one that was rescued from covering up a tractor engine to keep the frost off.

Not all the quilts went to the UK, Maxine has documented quilts that went in the immediate post-war period to The Netherlands, Belgium, and France. Maxine also knows that in a separate initiative the Mennonites sent quilts to Germany with the thinking that they would send them where they were needed, irrespective of the politics. Maxine would like in time to find a good home for her collection of quilts – a home that is able to take care of them properly:

I mean, it would have to be a textile gallery or a gallery that’s, you know, interested in Canadian history. You know, they’re welcome to the whole collection. But I must say I don’t hold out any great hopes for that, but if anybody has any suggestions, you know, I’m open to receiving your queries.

Maxine is also quite clear about why these quilts and the other items that were made by women have been so completely overlooked.

I think part of that is because it’s women’s work and women who didn’t have any official status during the war. I mean, you have to remember in London, the Memorial went up to animals in the war before one went up to women in the war, which kind of sums up the general attitude.

And even now in London, the memorial to women in war commemorates those women who wore a uniform, In Canada, there is a single memorial to the women who died in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. There is nothing in either nation to commemorate the millions of women who contributed their textile skills and domestic labour in any crisis. To me, the story of the quilts and the other comforts is part of the fabric of Canada’s story as a nation – just as much as maple trees, the Mounties, and ice hockey, but at the moment it’s a missing chapter: Here’s Joanna

And it was as if that anything that was related to domesticity was set aside or tucked away or hidden or not talked about almost like embarrassing to say, oh, and women sewed all through the war, women, sewed women, knit women, crochet women made things all through the war. They were busy, they made 55 million items. We’re, we’re not talking about that because we wanna talk about what women did outside of that, that actually helped them move forward into a more balanced role in our society, which we’re of course still seeking. But somewhere along the way, we’ve sort of tossed aside that actually some of this making might actually be very good for us and could actually play a role in our lives now.

Joanna knows exactly what her grandfather did in World War One – it is all archived and recorded, but her Grandmother’s record is blank – she looked after five children, ran the farm, and still made time to gather with her local community to make items for that war – but no-one recorded that. The story of these quilts is one with many layers and this episode of Haptic and Hue does little more than scrape the surface of what could be told, there will be tales of comfort and resilience, but there will also be darker sides to this, and I hope one day, there will be a full history of the quilts, how they came to be made and the impact they had. The work that Maxine, Jan, and Joanna have done has all been painstakingly assembled from primary sources: many hours spent looking at microfilm in libraries, sorting through old files and digital records, hunting down marginal references strewn like tiny bright beads across the world. It needs now to be gathered up and restored to its proper place as a complete story in its own right rather than being part of everyone else tales. At the start of this episode, I said the quilt my mother and I found 30 years ago had an unusual handwritten label on it. The Canadian Red Cross frowned on quilts being ‘signed’. They were supposed to carry an anonymous label that said simply gift of the Canadian Red Cross. But happily, sometimes rules got broken: our quilt said: WVS, Winona Circle, Grace United Church, Gananoque, Ontario, Canada. After I had told Joanna about it she managed to find out more about it in a week than I had done in 3 decades.

So I researched where the Winona Circle was, and the members of the church helped me to find reference to this in a history book about the church and the Winona Circle was a missionary auxiliary, and it was named for the pastor’s daughter, Winona Pitcher, and this missionary auxiliary met in the evenings and made items for missions starting around 1910. So they would’ve been working through the First World War as well. And they were also still meeting during the Second World War. We, I also found by reading the Gananoque Reporter which was the community newspaper still in existence and I think it started around 1860. It was very much a community fixture. And so it was a great resource to track the work that was being done for the Red Cross and for the people of Britain by the community. And they, the Gananoque Reporter reported in it what people were doing or making or giving. So on the front page, it would say so and so donated this much money, this group donated five pairs of socks and so on. And it would list this every week. So I imagine that this was great encouragement for people to be a little bit competitive and go, oh, look what my neighbour gave. I need to <laugh>, let’s see what we’re going to find and give. I, I, I think it’s a, a little bit of fun. I haven’t found that in any other community.

Joanna also found the grandson of one of the women who had been a member of the Grace United Church during the War. Paul Harding is still a member of the Church today and happily his grandmother, Annie Scott was a rule breaker too. She discretely pinned her name and address to the quilts her group made and as a result, got some letters written back to her. She kept them and her grandson has them still: they are lovely to read: A note from Alice Waldren in London in 1942 says thank you for a knitted rug given to her elderly mother adding: “We lost our house through the raids and then a second home and all our things.” A typewritten letter from Muriel Butterworth, the Area Organiser of the Women’s Voluntary Service in Holmfirth, says: “Thank you very much for the beautiful quilt which reached us yesterday. I wish you could have heard our evacuee’s delighted cry of; “Oh how lovely” when I took it to her and she gleefully put it over a Government blanket on her bed. I told her from whom it had come, and she said: “Fancy thinking of us from so far away as all that.” This Mrs. Heel has four children. Her husband is in the RAF overseas. Her house and all her furniture have been completely destroyed.” There is even a letter from Clementine Churchill in Mrs. Scott’s collection, which begins: “I am writing to add my personal thanks to those of every man woman and child in these islands for the gifts which you have sent to help us.” After thirty years of taking care of the quilt that was handed in on that cold winter’s day, deciding what to do next wasn’t difficult. In early November we packed it up and sent it back to Gananoque – around 80 years after it had left there for the UK. We thought it was right that the town should have its own history back so that it could be enjoyed where it was made, – it is a very small thank you for all that labour that meant so much to people in such desperate circumstances.

So on November 11th, the quilt arrived back in Canada in time for our Remembrance Day. And on November the 11th, we had a small ceremony at the public library where the quilt was received back to the community. The mayor was there and the Councillor and members of the library and members of the community and the church who had been involved in helping me with the research. The quilt is now in the custody of the Thousand Islands History Museum, which is in Gananoque. And they are working through the process of accessioning the quilt, but it will, they’re very happy to welcome it into their collection. And people have been calling the museum asking to see the quilt already because of the publicity that was received in the newspaper. And they’re very anxious to see the quilt, but it’s not available to view at this time.

But it will available soon for this generation of Canadians to see, and I hope for many more to come so that they have a better understanding of the different ways in which people, particularly women who are not in uniform, respond to crisis. Joanna is recording the quilts that have been repatriated to Canada, and so far this is only the 12th quilt that she has found which has come back to Canada. There may be others but sometimes the extensive lack of knowledge of this astonishing war-time operation means people simply don’t know what they have. Every one you heard in this podcast hopes that is now changing. This episode has been a long time in the making and it would not have happened without Joanna’s determination and research skills – thank you – you are a true champion of the quilts – they are lucky to have you. Maxine and her research group have done an enormous amount to rescue the quilts from the dog basket of history – just before it was too late. If it wasn’t for them we would be talking about a handful of quilts, not 250. Jan Hazzard and Phyllis Vanhorne are remarkable witnesses to events that are rapidly sliding out of known memory – thank you for sharing them with me. Thank too to Bill Taylor for Editing and producing this episode. The hands that made the Winona quilt have passed on by now. But the quilt remains as their war record, and their considerable contribution at a time of great need. It also survives as an example of the ties that connect people in difficult times. I find it remarkable that these women and children cared for individuals suffering and displaced in the Second World War, people they had never known and never would know, but were able nonetheless to console. We should honour them as much as we honour those who served. This episode of Haptic and Hue is dedicated to the millions of nameless women, and some men, of all nations who have knitted and stitched, sewn and quilted in wartime and crisis to console and comfort those who suffer and work. We should remember them better than we do.

If you would like to see any resources relating to this episode please go to www.hapticandhue.com/listen where you can find pictures links and a full script. Including information on who to contact if you have a Canadian Red Cross quilt or a story about a quilt. This is the last episode of Haptic and Hue in this series, The Chatter of Cloth. I will be back later this year with another season of Tales of Textiles after a break and a chance to think about what stories come next. If you have an idea that you think would make a great episode send me an e-mail or drop me a message on Instagram, I’m always interested, and if you find a great poem or a piece of writing about textiles or textile making let me know – you have no idea how hard these are to find. Thank you, as ever for listening to these tales. If you would like to contribute to making Season 4 a reality please feel free to Buy Me Coffee. It all helps. The Haptic and Hue Bookshop – which sadly functions only for those in the US and the UK will remain open and online at all times – there are some great books there. I look forward to your company for the next Season of Haptic and Hue’s Tales of Textiles.