The Tangled Tale of Tartan

Episode #41

In this episode of Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, we look at where tartan comes from and how it acquired its many meanings and controversies, why some people love it and others hate it. Tartan is a textile of duality, able to hold many ideas within its simple grid design. It has a history that has spread out across the world and taken a sense of what it means to be Scottish with it.

But there is more than history to tartan: we also hear from a bespoke kilt-maker, who designs and registers her own tartans. She creates modern tartans able to embrace new definitions of identity and community and expand far beyond the Highland glens they first sprung from.

All of this has been put into context by the first exhibition in living memory about tartan in Scotland itself, which opened in April 2023 at the Victoria and Albert Museum in Dundee, which we went to see as part of making this episode.

The people you hear in the episode are:

Kirsty Hassard, Curator, Victoria and Albert Museum, Dundee, you can find her on Instagram @kirstoir, and you can find out more about the V&ADundee’s Tartan exhibition at https://www.vam.ac.uk/dundee

Andrea Chappell, bespoke kiltmaker who runs Acme Atelier, you can admire her many beautiful kilts on her website or on Instagram as @acme.atelier.

Bill Taylor who is the co-host of Travels with Textiles on Friends of Haptic & Hue and Editor and Producer of this podcast.

If you are interested in reading more about the cultural history of tartan then there are two books that I enjoyed.

Tartan by Jonathan Faiers which can be found in the Haptic and Hue US bookshop and the UK Bookshop.

From Tartan to Tartanry, Scottish Culture, History and Myth, edited by Ian Brown, which I would advise buying second hand on a site like Abe books.

And if you want to look up the Scottish Register of Tartans you can find out exactly who has registered what tartans and why. I find the section that says new tartans particularly interesting.

Kirsty Hassard, Curator, Victoria & Albert Museum, Dundee

The Many Patterns of Tartan

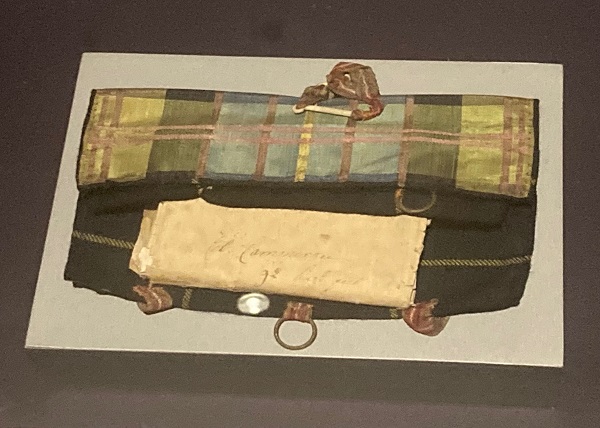

The Tartan Huswif Given to a Soldier for Protection by Unity Matthews

Bonnie Prince Charlie in Tartan

Scottish Emigrants Waiting to Leave Home in Tartan

Portrait of George IV

by David Wilkie marking his trip to Edinburgh

Queen Victoria’s Daughters in Tartan.

Mud Splattered Kilt from World War 1

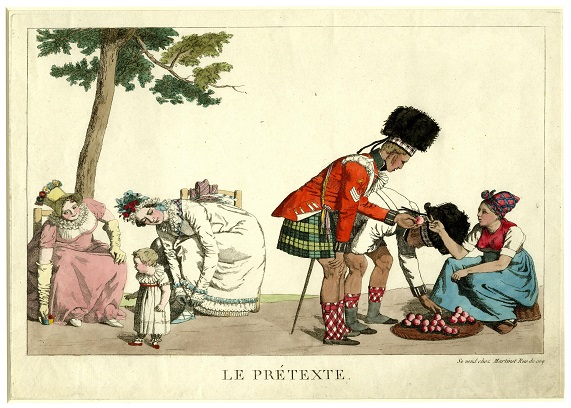

Tartan arrives in Paris 1815. Print from the British Museum

Tartan in Paris – Satirical Print – British Museum

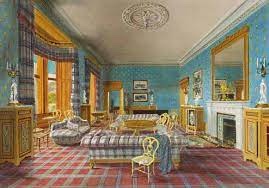

Balmoral Decorated in Tartan

Acme Atelier’s Tango Kilt – made from waste Tartan, exhibited at the V&A

Andrea Chappell, bespoke kiltmaker who runs Acme Atelier

Andrea and her sister dressed in tartan for school.

Andrea on the right.

Andrea and her mother, wearing kilts that include fabric from Andrea’s Grandfather’s Military Black Watch Kilt.

Trujillo Tartan made up into a kilt – Acme Atelier

Trujillo Tartan warp on the loom – Acme Atelier

Trujillo Tartan on the loom – Acme Atelier

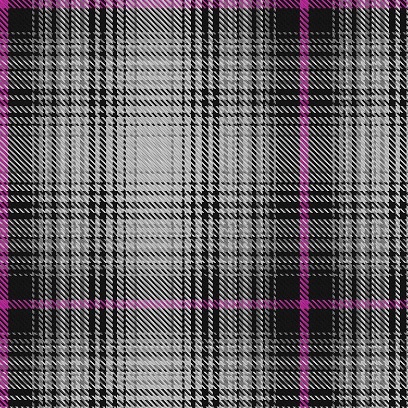

Victoria and Albert Museum’s Own Tartan

Tree in Forres from which Andrea is designing a Winter Tartan

Bill Taylor

Script

The Tangled Tale of Tartan

JA: There are few fabrics in this world that are as simple and at the same time as complicated as tartan. It is designed using a simple grid – but isn’t easy to weave – it takes focus and concentration – I know I’ve tried! But it is in its meaning that it becomes truly complex, able to express simultaneously a series of contradictions. It is both an emblem of Highland rebellion and the uniform of the military forces that opposed them. It is a high fashion fabric seen on the catwalk and the mark of a shepherd from the hills, it is the symbol of a tight family clan network based in a small geographic area and also a global brand that has travelled the world. Tartan is many things and everyone has their own view of it. Join me in this new episode to explore the many shades of Tartan.

Welcome to Haptic & Hue’s Tales of Textiles, my name is Jo Andrews and I’m a handweaver, interested in what cloth tells us about ourselves and our societies. Often the stories and information that textiles can give us are ignored and we lose a whole dimension of human experience. This podcast is about trying to restore that.

Bill: So there’s that constant shape-shifting thing, and for some people, tartan still, where it’s relevant at all, is an image of repression, for some people it’s an image of belonging, of courage, of important family ties. The myth of tartan is constantly, even in our time, being reborn, redeveloped, refreshed. And it continues to mean all sorts of things to all sorts of people.

JA: That’s Bill Taylor, who some of you will recognise as my co-presenter for the separate Friends of Haptic & Hue podcast. He was born and grew up in Scotland and has always been a tartan sceptic until we went last month to the new exhibition called simply Tartan. It’s at the Victoria and Albert Museum in Dundee and it’s the first exhibition about tartan in Scotland in living memory, which is extraordinary. One of the curators is Kirsty Hassard.

Kirsty: I think the beauty of tartan to me is that it has some sort of resonance with everyone. So, whether you absolutely hate it, and think that it’s super kitsch, it represents a Scotland that doesn’t exist anymore. Or if you celebrate it and you wear the kilt, and it’s a massive part of your national identity. I think it’s what’s really interesting is that everyone’s got an opinion on it and everyone has some sort of resonance with it, even if it is a sort of resonance of I really don’t like that, and that’s got nothing to do with me, you’ll have some sort of like, opinion on it. I think for me personally, my family are Scottish, I’ve got, like, from as far as I’ve been able to trace back genealogy, I’ve got Scottish ancestors dating back to at least the 17th century, but my family don’t have a tartan, and I didn’t really have a strong association with Tartan until I did this exhibition I think it’s, yeah, really opened up my eyes, I would say, to maybe my own identity and how tartan has connected to that. Yeah.

JA: But just as tartan is a cloth of contradiction and as likely to be found on a Vivienne Westwood dress costing thousands of pounds as on a 70s boy band like the Bay City Rollers, there is no one definition of anything in this story, and every time you think something is certain you find you have opened another box of thistles. Here’s one: where does the word Tartan itself come from?

Kirsty: So that’s much debated, but it’s supposed to come from either French or Italian ‘tartaine’. And they think at some point in the 15th or 16th century that was adapted into tartan. And actually, one of the earliest objects that we’ve got in the exhibition from 1530 is a pair of tartan trews being ordered for King James the Fifth, the father of Mary Queen of Scots. And that refers to, I think that refers to tartaine or tartan. So, I think at that point in history, people would have an understanding of what tartan was, but the name would probably still be quite, quite new.

JA: And in French tartaine means a checked cloth. Kirsty defines a tartan as two different colours of threads that cross over to make a third colour on a grid pattern. The origin of tartan is another box of thistles, but a scrap of fabric that has survived 500 hundred years in a bog in Glen Affric has just been researched and carbon dated to the 1500 hundreds:

Kirsty: What makes it the first real tartan is that when you look at it, although obviously you know, it, it’s been very discoloured by being in a bog. You can see distinct parallels and similarities with what we refer to as a tartan in 2023. So, you see those two strands of colours that are crossing over to make a third colour. You see the same rules that designers of tartan and weavers would adhere to in terms of the idea of colour and the pattern and the proportion and all those are really clear, although it’s, you know, obviously it’s not even like a length of, of tartan. It’s still a fragment, but you still see those yeah, those three distinct rules present.

JA: With those basics we come forward two hundred years to the 1700s – the turbulent century of many changes and revolutions, America declared its independence for one, but it was also a time of great ferment and revolution in Scotland that threatened Britain as a whole. This was a conflict in which tartan played a central role. In 1745 a serious rebellion led by Bonnie Prince Charlie broke out in the Highlands of Scotland – the Jacobite Uprising. The last of the Catholic Stewarts to try to take back the British throne led his troops, dressed in their own clan tartans, south to try to take the throne from the Protestant Hanoverian Kings in London. At first, they had stunning success before the Highlanders were brutally put down by the British army at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. In defeat their tartan became a marker of dangerous rebellion, here’s Kirsty:

Kirsty: And what is really interesting with the Jacobite uprising, in particular, is how it’s used so overtly as a political textile. And obviously that’s carried through until the modern day. You know, you, you still see it being used as its forms of, of propaganda. And particularly post Culloden. So post 1746, when obviously the Jacobite Uprising is repressed and Bonnie Prince Charlie leaves Scotland and goes into exile. There’s very much that idea of martyrdom in this sort of lost cause. And around that you get lots of these little tartan fragments that were gathered by supporters of Bonnie Prince Charlie, and then kept either in private collections or then eventually museum collections and are really prized possessions and are still revered almost as almost like religious relics in the modern day. Running parallel to that is obviously this suppression of Highland culture that happens post 1745 and 1746 where there was a British Government ban on important aspects of Highland culture. So, for example, the speaking of Gaelic was banned, the playing of the bagpipes was banned and Highland dress was banned.

JA: But at the same time the only place you could legally wear your tartan was in the British army, which started recruiting Highland Regiments and, yes dressed them in kilts:

Kirsty: And that was one of the ways you could get around wearing tartan would be if you wore it as a form of military dress, which is why you still see in the 1750s and 1760s examples of sort of prominent members of Scottish aristocracy wearing tartan because they’re wearing it as a form of military dress. But I think that’s sort of that really interesting sort of the polarity of that relationship between how tartan was used. In the kind of latter end of the 18th century it is a textile technically of repression, you know, by British government forces. So we’re repressing a lot of Highland culture. A lot of them were wearing tartan themselves, which is obvious still seen as been a sort of iconic part of Highland culture.

JA: Kirsty says that this duality in tartan came up over and over again in many different contexts as they put the exhibition together:

Kirsty: There are letters from textile manufacturers to slave owners in the North Americas in the late 18th century where the slave owners or plantation owners are writing to textile manufacturers in Scotland, asking them for lengths of cloth and specifically tartan as a way to mark out that they own that particular slave. And then there’s also runaway slave adverts from the 18th century as well. As the title suggests that slaves would run away from their owners what they were wearing was recorded. And a lot of the time that was tartan. So by a sort of extension, you can assume that because it was such a popular textile that the textile that was being used to oppress and control these people was also probably being worn, but in a different way by the people who owned them.

JA: It took the Hanoverian Kings nearly 80 years to recover from their fright over Scotland, but in 1822 George the Fourth went to Edinburgh on a trip tightly stage managed by the novelist Sir Walter Scott and tartan took centre stage:

Kirsty: And its a way to welcome George to Edinburgh using tartan as a, a way of almost I was gonna say propaganda. Propaganda maybe isn’t necessarily the right word, but, a way to sort of display Scottishness. And, it’s done in a very, very ceremonial way. There are records of the time of the uniforms and the sort of ceremonial costumes that were commissioned for it. So, a lot of the textile manufacturers in Edinburgh, and particularly outside of Edinburgh, Wilsons of Bannockburn, being the main one, were just sort of overwhelmed with work, because the amount of lengths of fabric that they were having to produce. But in terms of legitimizing it after its sort of rebellious reputation post 1745, it definitely does that, because George the Fourth famously wears a kilt and is obviously parodied for that, there’s lots of satirical prints of how he wore the kilt completely wrong and wore, like a short version of it, more with tights, et cetera. But yeah, in terms of legitimizing it, particularly for the British royal family and that sort of adoption by the British royal family, that’s when it really starts as, yeah, 1822, you can definitely trace that relationship to Queen Victoria in particular adopting it 20 years later.

JA: And it was Queen Victoria’s husband, Albert, who bought Balmoral for her as her Scottish country home, where, to put it kindly – she went tartan mad.

Kirsty: Balmoral is seen as being a place of retreat and away from court life in London. And yeah, she refers to this in her journals, I mean, obviously, you know, it’s a setting, Balmoral is in a quite rural location. It’s quite remote. But it’s very much down to how Balmoral is decorated by herself and by Prince Albert. And obviously a huge amount of that is to do with tartan. So, one of the watercolours that we have in the exhibition is a watercolour of Queen Victoria’s bedroom at Balmoral and it’s got a tartan carpet, a tartan bed-hangings and curtains and table covers. And it’s that sort of protective or sort of, I think, comforting element of tartan that you see continually used in interior design to sort of communicate a particular message that really starts, arguably with Queen Victoria, at Balmoral, and obviously, her and Prince Albert wear items of tartan. They dressed their children in Tartan, their staff at Balmoral wore tartan. Prince Albert supposedly designed a tartan, the Balmoral Memorial Tartan.

JA: Once tartan was adopted by royalty – a connection that continues to this day – it filtered out across the grand families of Scotland and everyone who was anyone had a tartan, or often several tartans, made up for them. These often had very little to do with ancient tradition and much more to do with the Victorian’s eye for a good story and nice commercial opportunity. This brought, in time a strong reaction against tartan from many Scots themselves – here’s Bill.

Bill: I was a teenager in the 1960s in Scotland, and yes, a lowland coal mining village, working class village. I thought tartan had nothing to do with me at all. Tartan was for posh families. It was something that harked back to a sentimental idea of the Scottish past. And not only did I, did I not think it had anything to do with me, but actually I thought it got in the way of, of trying to establish a new cultural identity for Scotland. And I was impatient, and very conflicted about that thing I wanted because I was a young man. I wanted Scotland to be seen as an exciting small nation with enormous possibility. And everywhere I went, it seemed, I saw tartan shortbread boxes tartan scarves, people from other parts of the world talking endlessly about their family heritage and tartan’s expression of that. And it seemed to me as a working class boy, that tartan was for posh people. That tartan was about the past. That it was about these, you know, these things that had nothing to do with me. Especially the idea that tartan was a marker of your connection to a landed aristocracy somewhere several hundred years ago in history, and certainly in a coal mining village in Southern Scotland that had absolutely nothing to do with us.

JA: But the exhibition showed Bill that tartan has something to offer beyond this:

Bill: But what I learned at, at the V & A exhibition in Dundee was that tartan, the meaning of tartan is a constantly shifting thing, that even to this day it means all sorts of things at the same time. As you know, I was very struck by this idea of rebellion and oppression. So it can be a marker of the state’s oppression of people who don’t conform, but it can be an act of rebellion for, you know, for punk bizarrely, you know, Doc Martin’s boots, Vivian Westwood. Can you imagine punk saying, oh, this is an expression of my sort of refusal to conform to everything else that’s going on in fashion and social life? Thanks to that V & A exhibition the meaning of tartan became much, much more complex. And actually, I was able to, if you like rid myself of my youthful prejudice and understand a new complexity in tartan. All over the world, tartan is revered for all sorts of different reasons and still has enormous meaning for a vast range of people who think that tartan is something special for their identity. And I wouldn’t want to take that away from anyone, but I’d love to see, and I think the V&A exhibition does this, I’d love to see the idea of tartan being continually updated and continually brought back to life.

JA And the other area where tartan has acquired new meaning is in its use as a military uniform. British soldiers have taken tartan on their kilts all over the world:

Bill: Remember how tartan in the military context started after the Jacobite rebellions in the 18th century, a form of civil war in the UK and Scotland. It must have been a very frightening and dangerous time. The Crown, the British State set up Scottish regiments that were particularly designed to dampen down the rebellion. And they were deliberately used as an act of psychological warfare. They were deliberately dressed in tartan because the Highland clans who’d been part of the Jacobite Rebellion were not able after their defeat to wear Highland dress, that was forbidden by law. But the new Scottish regiments that were designed to keep the rebellion down, were specifically dressed in tartan. So, it became an image of the power of the state against any rebellion. And since then, obviously those Scottish regiments have fought all over the empire with British forces. And that tartan for them has become a marker of their courage, of their history. So that’s another example of the continual shape shifting of tartan. So many of the forces who did wear tartan after the Jacobite Rebellions gave their lives in dreadful circumstances, in times of war, for the British state. And you can only think about their courage.

JA: In time Soldier’s tartan begins to acquire a mythical status – the fighters who wore it were feared, but the tartan itself was seen as gracing protection to those who wore it. One of the most poignant items in the tartan exhibition is a Cameron Highlander’s kilt still mud-stained from the trenches of the First World War.

Bill: And he came home wounded, nursed back to life by his family, and his family said, let’s keep the mud of the trenches on the kilt as a marker of the sacrifice of all these men in war. Because these Scottish regiments had a sort of belief, certainly a hope that the tartan would be a sort talismanic defence against death, which of course it wasn’t. And I was haunted by that idea.

JA: And there’s also a small tartan sewing kit or Huswif made for a soldier departing for war as Kirsty explains:

Kirsty: So it’s like a little sewing kit that soldiers would take with them in the army, so they could do basic mending on their uniform. And the huswif that we have in the exhibition was, was made for a soldier by someone called Unity Matthews. And this is in the early 19th century, and the soldier was going off to fight during the Napoleonic war, and she made him this sort of little I guess like a purse or a wallet of tartan and added in seeds that were meant to be for protection. And then yeah, gave him this as he went off to fight I guess as a kind of, way of keeping him safe, and, and away from harm, which ultimately I don’t think did work. He did in fact pass away. But I think it’s all about that sort of powerful meaning of tartan and this intrinsic value and what it can do as a textile protection

JA: But it is via the military that tartan begins to go international. It first starts in 1815 with Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo.

Kirsty: And then subsequently Scottish regiments being stationed or Highland regiments being stationed in Paris and obviously wearing their kilts, and in regimental tartans, and French women being completely fascinated by this. And then subsequently these tartans making a big appearance in fashion plates of 1814 and 1815, some of which we have in the exhibition. So women wearing tartan boots or tartan shawls or, or tartan dresses. And we think, yeah, this is sort of directly inspired by yeah, by the sort of military obsession then becomes a part of everyday dress.

JA: And once it enters the lexicon of fashion – tartan really never leaves it. Coco Chanel and Else Schiaparelli both adopted it in the 20th century and then famously in this century, Vivienne Westwood was one of its great fans. But it was a different movement altogether than gave tartan truly international wings and that was the great emigration from Scotland in the 19th century – the creation of the Scottish diaspora in Canada, America, Australia, New Zealand, Africa and India. They left home but they often took home with them in the form of tartan, and in doing so they created a new relationship with tartan – one that spoke of a connection with home and long-lost family, something simpler and more joyful:

Kirsty: I don’t think I can quite define it, but I think North America has got a much more almost unashamed relationship with tartan than, than we do in Scotland or, or certainly Britain. They’re much more forward at celebrating it. You know, the fact that you know, as we record this, it’s just a week after Tartan Week, which is obviously this big celebration of all things tartan in, in New York, and, you know, people come from all over the world and a delegation is sent from Scotland to celebrate it. Whereas I don’t think in Scotland we quite have that same sort of celebratory relationship with it. I dunno if it’s just because in Scotland maybe it’s just more part of everyday life here and it’s not seen as something to sort of showcase on that scale.

JA: And as our world changes in this century tartan’s simple grid and pattern is expanding and transforming to express new ideas of family and connection:

Andrea: One of the last ones I designed was actually for a local Scottish family here who are a mixture of Scottish and Colombian <laugh>, an interesting mix. There was a request to bring in the Scottish Glens and the Colombian coffee plantations. So we were mixing greens with purples and heathery kind of colours. Then there was this over check request that the Colombian, the yellow of the Colombian flag had to be incorporated. But the most specific part of this tartan cloth that you can’t actually see is the fact that the father, the head of the family was a salsa dancer. And the sett, so the pattern repeat, and each of the stripes in the tartan is based on the beats of the salsa. So when the, the feet move, there is a line. And when you, you are still, there is a block. So that’s how I designed the tartan and it’s registered on that basis.

JA: That’s Andrea Chappell, a modern kiltmaker and tartan designer who works in Forres in North East Scotland. Andrea was born in the south of England, but with Scottish ancestry Her kilt journey began with quite another life as an exhibition designer. Every time she completed a project she decided to commemorate it by commissioning a kilt from an Edinburgh kiltmaker:

Andrea:And then every project that I built, I went back to him <laugh> it started with a sort of just request for, well, could I have a red one? Could I have a yellow one? Could I have a denim one <laugh>? And then it started to get a bit more elaborate, and the places that I was working were also getting a bit further afield. And the projects were, I kind of went onto a grander scale. And so I would turn up with cloth that I had purchased where I was building these projects and would start to embed more things. And it got to, I would say, 20 years on. And I have I had then a, a wardrobe off of kilts and was wearing these on a daily basis, and they just became my uniform.

JA: And then just over seven years ago she decided that she wanted to re-establish her connection with making and by chance she saw an advertisement for a Kilt School.

Andrea: And for me, it made total sense when I saw a little advertisement for the Keith Kilt School, and I thought, ah, well, there we are, this, of course, that’s what I should do. And I was not in anyway, even a dress maker. So, it turned out that that’s actually more helpful than not in the making of the kilts, because traditionally made kilts are all hand stitched. So, you don’t need to know how to use a machine whilst you, you do need to understand the form of the body. You don’t need to understand the construction of garments per se. You through the hand stitching and the, and the construction of the kilt understand that particular process in a very specific way.

JA: She has joined a craft that is now officially registered as endangered in the UK. Her orders often come from people celebrating a life event or milestone.

Andrea: The kind of most traditional point at which kilts are commissioned is either a wedding or often a graduation, which kind of aligns with their 21st birthday. Those are sort of the longstanding traditional points. But I’ve found, in particular with women, a lot of the time they’re commemorating a, a big birthday. I’ve had commemorations of significant achievements like, you know, a PhD, I’m just doing one for a gentleman who is a Scottish Nigerian. So we’ll be weaving in some element of Ashoke, the hand woven strip cloth in cotton into a tartan. And we will be making something that he’ll be wearing when he’s given his MBE.

JA: Which is a British Honour for service to the community. One of the wonderful things about Andrea’s work is that she is an expert at mixing different materials in a kilt – partly for reasons of sustainability – she doesn’t make everything from new – but partly to give the kilt an opportunity to say something truthful about the person who wears it.

Andrea: So you are, you are making a length of nearly nine meters in, you know, eight to nine meters. So it’s a hell of a lot of cloth in a traditional kilt. So, as well as the sustainability aspect to it, there’s also obviously the lovely thing that, like this Nigerian gentleman, he would like to celebrate both aspects of his heritage. It’s a lovely thing that that cloth does, where we have this combination that we can express that is embedded in us all. It’s not just one thing. We are not just Scottish, you know, very much like my myself, I would say I am this, this lovely sort of woven mix of the British Isles. And so why not bring that together physically in different cloths, because it’s just a, a lovely way to express how individual we, we all are and, and made up of different parts.

JA: Subduing nine metres of cloth is a skill all of its own:

Andrea: You’re fighting cloth until you’ve really got the pleats in, I mean, in most cases, the technical alignment and shaping of the pleating when you are going through that particular part of the process is, I would say probably the most technical element and the most difficult element. The needles we use are very small and thin and the thread is very strong and thick. So actually <laugh> for me, it’s, it’s more threading the needle <laugh>, as basic as that sounds, but my eyes are getting worse and worse. So yes, it can be basic <laugh>, but you, you are taking one flat length of cloth and moulding it to a body shape through a mixture of, of pleats and flat areas. So it is quite technical to interpret the cloth and interpret the body, the shape of the body into the cloth only through pleating.

JA: And one of the most technical parts of working with tartan is deciding how to pleat the pattern a small difference here – makes a radical difference to the finished item.

Andrea: Well, there’s, there’s two ways really that the kilt can differ quite dramatically using exactly the same tartan. One is how you, the kilt maker is interpreting the pattern. You can pleat to the stripe, the block, the half block. And some people call it other things, but what that is doing is that’s changing how the tartan appears in the pleated section, making it distinctly different from front to back. And each pleat would be set up for the shape of the pleat to be in a specific area on the tartan that repeats itself through each pleat. Or sometimes it alternates potentially. So, what you might be doing is you might be looking at a tartan that has a red over check in it and a yellow over check in it. And you might be saying, I’d like to bring out more of that red. So, each pleat would align on the centre of the red line. And that would give you a pleat to the stripe. You might then start to, to add more into that and take a different part of the tartan, and you might choose to alternate one sort of landing point, if you like, in the centre of a pleat with a different landing point on the next pleat. And that will change the depth of your pleats, and you might alternate the depths of your pleat. So that’s the sort of aesthetic change, but there’s also differences in the ways in which you can pleat. Many people only really see knife pleating as, as a sort of traditional kilt, but in actual fact, kilts can be pleated as a box pleat, as a double box pleat as a Kingussie pleat, and as a Military Roll pleat. And all of those are traditional kilts. And they are designs for pleating that have been used for hundreds of years.

JA: Tartans are listed with the Scottish Register of Tartans – a Government body that keeps the complete list of official tartans. Anyone can search it. Each tartan must be unique and have its own story. These days hotels, cities, commercial companies, public institutions, football clubs and even museums like the V&A have their own tartans. The V&A’s is based on their extraordinary building in Dundee which was designed by a Japanese architect, the tartan is grey, white, and black with flashes of shocking pink inspired by the couturier Else Schiaparelli’s love for the Highlands of Scotland. Back in Forres, Andrea is also designing new tartans too:

Andrea: Another one is actually one that I’m designing at the moment for the Atelier, for myself, so that we can offer something about the area that is changes through the season. So, there’s actually four, and each of them are things to do with the region of Moray that I live in, that are specific to here. So, we have a very, very clean air and a very beautiful lichen, a very beautiful moss that is actually a protected moss and an incredible coastline. So all of these things are coming into the design of a tartan for each season that reflects Moray. The first one is Winter, and it is a particular tree that I pass every day on my dog walk. And it’s the colours within this tree and the lichen that is forming over as it, as it gets wet with the rain. So, it’s a kind of burgundy and peaty brown base that brings the bark in. And it has almost blues, a kind of slatey blue grey with very kind of pale greens and a very sharp mossy green through it as well.

JA: And that will be followed with Spring, Summer and Autumn. There is no doubting tartan’s enduring appeal and Andrea thinks that comes from the idea of Scotland.

Andrea: I think it, it’s because they can find a connection to either the cloth or, or the country. You know, there a lot of people will say, I, I love Scotland. And there are many tartans that can be worn that are not clan tartans that can give you that connection with Scotland. And I think there’s just that recognition that, and, and hopefully as well the exhibition has highlighted this in the broadest of senses that there is a bit of that in all of us. You know, there is a connection there with that cloth in, in many, many different cultures outside of, of our shores.

JA: And for me that is part of the puzzle here. Scotland is not the only culture that has developed patterns and weaves based on a grid, Indian madras, cloth from the hill regions of Myanmar, even the familiar and much-loved blue and red pattern of the Masai plaid in East Africa, so why did Scotland come to claim this? Here’s Kirsty.

Kirsty: I think a lot of the heritage of tartan really chimes with the history of Scotland, or the industries that are really strong within Scotland. So, you know, the fact that the woollen industry being able to move to industrialization and sell on a kind of mass manufactured scale in the 19th century, at that point where this idea of Scotland was being sold to the world. I guess like trading links and market links already existed in Scotland at the time when tartan was becoming prominent. It’s so interesting because obviously if you go to most countries, they’ve got a version of what we would call a tartan, but obviously, to them, it’s a completely different design history or design trajectory. So yeah, as you say, Madras, which is not a tartan. But some people conflate it with tartan. Globally, there’s hundreds of, hundreds of different grid textiles that may look like tartan but are completely different. But I dunno, essentially it might just be good marketed to be honest, that <laugh> that did it for Scotland.

JA: And part of what Kirsty calls marketing is a good story, and whatever else you think about tartan, it is a material with a multitude of intricate myths and meanings behind it, that track and trace their way through history and continue to decorate and give sense to our lives today.

Bill: Tartan all over the world has a whole range of messages. And let’s not forget the important one. A lot of the time it’s beautiful and a lot of the time it’s fun. But behind all of that, it’s another example of how cloth speaks probably more directly, more powerfully than most other things about our past, our present, and our relationship with history.

JA: Thank you for listening to this episode of Haptic and Hue, and a huge thank you to Andrea Chappell, Kirsty Hassard and Bill Taylor for their reflections on Tartan and its many meanings. If you would like to see pictures of some of the events and tartans they have spoken about in this podcast, or read a full script, you can find them at Haptic and Hue’s website at www.hapticandhue.com/listen.

Haptic & Hue is hosted by me Jo Andrews, and produced and edited by Bill Taylor. It is an independent production supported entirely by its listeners, who bring us ideas and generously fund this podcast via Buy Me A Coffee, or by becoming a member of Friends of Haptic & Hue. This keeps the podcast truly independent, and free from advertising and sponsorship. It also brings you extra content every month and we have just posted an interview with the Head of Studio and Standards at the Royal School of Needlework about her experience of working on the embroidery that was on display during the recent Coronation of King Charles and Queen Camilla. If you would like to hear this or listen to any of the other interviews and podcasts posted there you can find out more, on the website at www.hapticandhue.com/friends.